The other day Bill Magie was on my mind all day. I had received a note from a friend that morning, and he told me that on a whim he had pulled A Wonderful Country, my collection of Bill’s stories, off the shelf and re-read a chapter about the 1920’s. Bill Magie (pronounced same as McGee) was a young man then, fresh out of Princeton, from a privileged upbringing in Duluth Minnesota, son of a well-known surgeon and doctor. He was trained in civil engineering and became a field boss for the water-level survey project in what is now the Quetico-Superior canoe country. Later in life, he would work as a timber cruiser, a pilot, a mining engineer, a wilderness guide, and an ardent canoe-country conservationist. Throughout his long life he was forever a storyteller, irascible and ribald and full of laughter — what his generation called “a live wire.”

Fifty years after some of Bill’s water-survey work, in 1977, I had transferred from the University of Montana and enrolled at a tiny campus on Lake Superior down the shore from Duluth. Northland College was fully in the grip of academia’s 1970’s La-La Land, complete with the option of “writing your own Major.” I took them up on this and designed a program for myself heavy on time in the woods and light on any such potentially useful realms of knowledge as computer science or taxonomy. Do I regret this? No, but it does make me chuckle.

My alma mater has recently gone under, drowned in a sea of debt, as have so many small post-secondary institutions in North America. From its small-town roots in the late-1800’s logging and mining boom of northern Wisconsin, I guess Northland never quite found its footing in the 21st century. And for another chuckle, you do have to wonder about a self-proclaimed “environmental college” with a logo featuring two swarthy lumberjacks atop a motto lifted from the book of Isaiah: “And A Highway Shall Be There.”

Somehow, in my first autumn at Northland, I learned that Bill Magie, canoe-country legend, was living just south of campus, along with his wife Lucille. In a burst of enthusiasm I telephoned him to see if we could meet in person. What began was a ritual that led to my first book-length writing project. Every week or two I would pilot my rusty green “Saab-story” coupe down to Bill’s place on the Eau Claire chain of lakes. He and Lucille would have me in and put out coffee and cookies or lunch while I set up a microphone and a cassette-tape recorder. I would ask a few leading questions about some aspect of Bill’s northwoods life, something like, “What size and shape of snowshoes did you like the best?” or “How did you stake out your dogteams overnight on the trail?” Anything, just to prime the pump. (In hindsight I think Bill had usually primed the pump himself a few minutes before I showed up, but I could never tell for sure.)

And the stories would start. One leading to another, hour upon hour, tape after tape, week after week. Later, back at my dorm room, I would set up the tape player, equipped with a foot-pedal on-off switch, load a continuous spool of paper into a Royal manual typewriter, and type away, pausing the recording with my foot-pedal so that I could keep up. I transcribed it all, word for word, and then began to cut — with scissors –and edit and arrange.

And now, re-reading some of those stories, I cringe and shudder.

Bill, like all of us, was a product of his time, of his upbringing, and of his experiences and his peers. Inspired by my friend’s note, I leafed through his stories myself the other day, there in the book with my name alongside Bill’s on the cover, and thought, “Wow, there is some — ahem — ‘colorful’ stuff in here!” Four-Bottle McGovern, Three-Tit Nellie, Old Deafy, and Big Fred Frederickson, to name a handful among many… and there are some bigoted, racist, misogynist innuendos sprinkled around, to name just a few sins. And yikes — my name’s on this thing!

And — and! — there are some heartwarming, happy, generous stories, characters, and anecdotes through it all.

Which brings me to one of my points. Put bluntly, it is my frustration with a groundswell of group-think that cannot seem to accept that good people can have, at some times in their lives or perhaps through their entire lives, some bad ideas and bad attitudes. And that many people have done or said some despicable things even while living notable and exemplary lives.

Ever said or done anything you now regret? And? Well?

What do you think we should do about that? Or what should now be done about the description by Samuel Hearne of the 1771 massacre at Bloody Falls, or of his guide Matonabbee’s treatment of his seven or eight wives – yes the same Matonabbee of street-names and lakes, businesses and schools all across the NWT? He of the admirable… and the abhorrent. Or about the by-gone, and some now rightly unpalatable, attitudes reflected in the books of people like Alexander Mackenzie, John Franklin, Warburton Pike, David Hanbury, Helge Ingstad, J.W. Tyrrell, Thierry Mallet, and on down the list of those who came through this country as wandering newcomers and colonizers, as cartographers and ethnographers and shameless plunderers, and as writers who wrote down what they saw, and sometimes added a bit as to how they felt about what they saw people doing. Some of it admirable, some downright abhorrent.

It’s a question, and it’s worth pondering. Those old direct accounts, written from daily experience in times we can scarcely imagine, documenting things moment to moment, are invaluable. What are we to do? Ban them? Burn them? Bury them? I hope not. Because just like Bill Magie’s stories, they weave together a backdrop for our own life and times in whatever part of the world we call home. I think it behooves us to seek out those old accounts, the layers of history behind whatever parts of the planet and its human history most fascinate us. To cringe, yes, at times, but to delve into them.

Okay, off the soapbox, chum. I’ll leave it there for now, as the interviewers and reporters like to say.

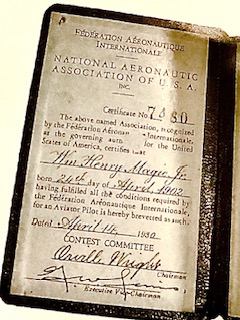

Just before bed the other night, the 24th of April, after thinking about Bill all day, I picked up the Raven Press edition of my book of his stories, and went searching for a photo. I knew that Johnnie, the publisher of that edition, had found a copy of Bill’s old pilot license, notable for one of the signatures it showed.

Finally I found it, on page 174. And then I really had to wonder about coincidence, since I had been thinking about Bill all day and I suddenly saw his birth date on the license: April 24, 1902. Well, I thought, happy 123rd birthday, old friend.

And yes, that’s Orville Wright’s signature. Orville, of Orville and Wilbur, and Kitty Hawk. Cool, eh? And hey, I wonder if Orville and his brother will someday come under fire for some remark or incident, unearthed by some diligent historian. I hope not.

I remember Bill telling me he had that license suspended for a few months early on in his flying days, for flying a Jenny bi-plane right under the Aerial Lift Bridge in Duluth harbor, on a dare. Boys will be boys. Clearly “hold my beer and watch this” did not start with the advent of the Go-Pro.

You must be logged in to post a comment.