A Horseshoer’s Great-Grandson Drones On (progressively?)

On the 27th of March I was flying alone over the blank white tundra of the upper Hanbury River country. It was a cold clear afternoon, 30 below zero, and I was thinking how lucky I was to be out there. 500 feet above the snow, doing about 85 knots in my little fabric-and-tube fart-cart airplane, with a cup of coffee at hand and some lively music piped in through my headset. My assigned task that day was — as it has so often been — simply to fly along and look constantly down and around, mile by mile, and to record locations and numbers of what the wildlife scientists lump together as “charismatic mega-fauna.” Big furry critters. On that particular day it was a survey for muskox, and my assigned straight-line east-west transects were around 80 miles long, spaced five miles apart. By the time I had logged nearly seven hours of this, including a quick and rough ski landing so that I could pour in some extra fuel from jerry cans, my butt hurt and I wasn’t feeling quite so lucky.

Yet even as I turned from the final waypoint and sped down the home stretch to McLeod Bay, I was thinking about what interesting work it is. I was thinking too of how completely it changed with the advent of GPS navigation. Over the past few decades countless advances have been labelled “revolutionary,” everything from dentures to digital cameras to hybrid drive-trains. Often that is just hyperbole and hooey, but for pilots there is no doubt that the advent of the Global Positioning System, or GPS, was a revolution.

Consider that as recently as 1990, a wildlife survey of the sort I have been flying these past few weeks would have involved a paper map gridded with carefully-drawn pencil lines. Once airborne, map in hand, the day’s flying demanded non-stop minute-to-minute human navigation, usually done with one finger firmly on the pencil line, a careful eye on the compass and the directional gyro and the landmarks below, with locations of animals jotted to a paper notepad on a small clipboard. Circa 2024, it’s “Send me the route files, and when we’re done flying I’ll send you the track and waypoint files.” If anybody today has to stoop so low as to type in coordinates for latitude and longitude, one peck at a time on a keypad, you’d think from their whining that they’d been forced to break rocks in the hot sun for a few hours. Yee-gads, the labor!

But we won’t stop here, with a little ski-plane and its bemused pilot glancing at a GPS screen and pressing “Enter” to record each sighting and create a waypoint. We never stop here, or anywhere, us humanoids. In less than two more decades, you can bet that this happy gig that I have spent so much of my flying life doing — that is, a lone pilot, or a pilot and a few hand-picked observers, flying straight lines over wild country, low and slow, watching intently out the window and recording what we see — will surely have gone the way of the old map-and-pencil. Because, of course, this is tricky and expensive and increasingly unpopular work. It can be cold, it can be boring, and it holds plenty of potential for human and mechanical error. There are new methods and tools coming that will put this form of knowledge collection into a bygone era. Another revolution.

Of course I am referring to drones.

A colleague of mine, who owns and manages a regional airline in the territories, and who clearly does not relish wildlife survey work, was waxing enthusiastic the other day in front of his hangar, as we both prepared to head out, each with a planeload of biologists and hired observers, for Day Five of a twelve-day moose survey. “You know, Dave, for less than the combined dollar value of these two planes, there is a drone being manufactured and marketed, right now today, with a Rotax engine and a six-hundred-mile range. You fit that sucker with an infrared camera and it will not miss so much as a lemming. Anything warm-blooded, it sees it. Fly it at a hundred feet. No observers, no fuel caches, no 35-below start-ups, no need to piss in a bottle or dehydrate yourself for the entire working day just to keep your bladder empty. Just settle in and control that baby right from your office chair. Slip out for lunch, come back, it’s still on course, it’s still takin’ down the info. It’s what’s comin’.”

Yep, I said. I know. I’ve heard.

And I am lucky. I have been paid to be out there, season after season, year after year, flying along, looking down and around at country that I first travelled by ski and dogsled, exactly 43 years ago (gulp.) Radford River, Campbell Lake, Crystal Island… Aloft, and often alone, on nice days with blue sky and sunshine, on crummy days with ice on the wings and windshield, pesky turbulence, white-outs and winds and patchy fog, and one especially memorable day when the engine knocked and coughed and sputtered and forced me to make a hurriedly selected touchdown on a snowy lake. Luckily the crew with me that day was unfazed by those festivities, and we soon had a fire going in the taiga spruce-patch while we waited for help to arrive in the form of a Single Otter on skis (from that same drone-enthusiastic friend’s company, two hundred miles away.) Kristen, back at home, had quickly arranged our rescue, over the satphone. That was March, 2010. Even then, when things went sideways, we already felt as though we were living in the future.

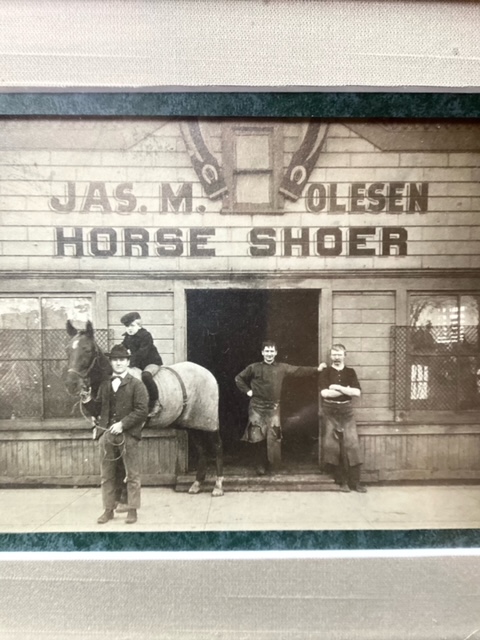

My great-grandfather was a blacksmith and a horse-shoer, who as a young man in 1890 emigrated from the Danish island of Samsø to the city of Chicago. I was thinking of him the other day — and of the drones that are coming to replace me, just as electric street-cars and the first Fords swiftly changed the streets of Chicago and put a serious dent in the demand for my ancestor’s horse-shoeing skills.

I doubt whether the residents of Chicago in 1925 truly missed the aroma of fresh horse manure on a muggy July afternoon. I do wonder, though, whether the desk-bound muskox-and-caribou-counters, seated at their monitors in the year 2044, programming and “flying” the drones and watching the tallies from the infra-red camera, will have managed to stay in touch with the country that is out there, mile upon white mile.

Will they have any real inkling about this cold pure landscape — how it feels, what makes it tick, how one watershed connects to another, or what mysteries it might hold?

I know this won’t surprise anyone, but on the chances of those drone drivers attaining or even aspiring to attain those insights, I am dubious.

The Hungarian sociologist Karl Mannheim, who lived from 1893 until 1947 — right through the horse-shoe to street-car revolution, and on to the birth of computers and nuclear fission, wrote that “For progressive people the present is the beginning of the future. For conservative people the present is the end of the past.”

There is more such work in the days ahead. Thankfully, I get to go do it. On this next round I even get to do it with Kristen, who will take high-res photos of muskox herds, from the ski-plane Husky with the window slid open. We will fly the lines, low and slow, mile by mile, in “real time,” as the folks in the know like to put it. (My great-grandpa and Karl Mannheim preferred to call it “the present.” Or just “now.”)

And we will remark to each other, every so often, that there is no one out here anymore. No one doing anything, in a space that dwarfs the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia, and is today emptier of day-to-day human activity than it has been since the ice sheets pulled away. My mind will wander, and I will ask myself: Are we at the beginning of something precise, sterile, safe, and efficient, or at the end of something direct, real, warm-blooded, and a bit risky?

In short, am I progressive, or conservative?

Well, yes.

(Here’s a photo from around 1910, in Chicago. My grandfather is the little fellow on the horse. His father is holding the bridle. Below that is the view out the side window of the Husky, at about 500 feet over the Mary Frances Lake area, the other day.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.